Guestrooms

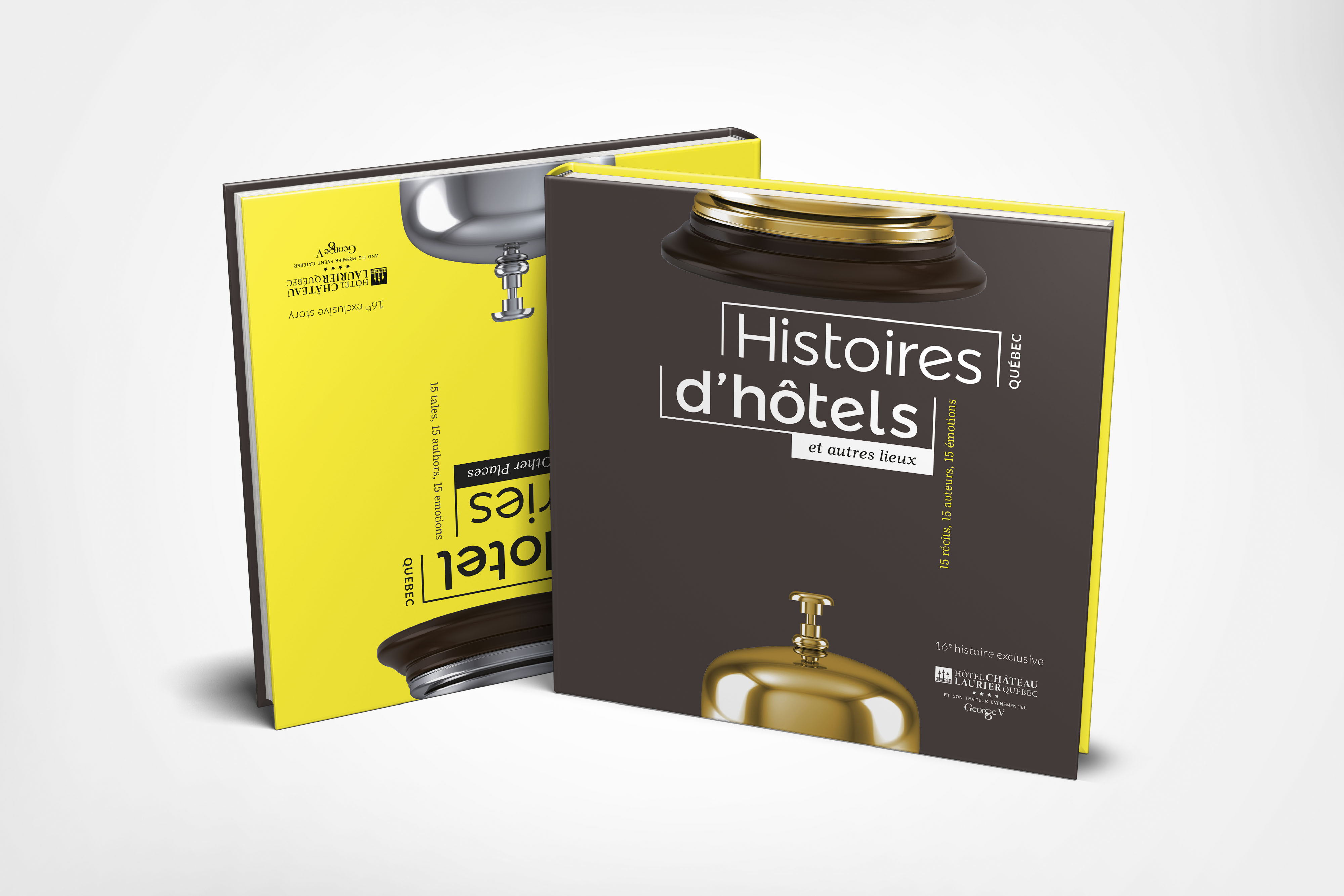

In my blog published in February, I was talking about a book that tells stories in different hotels. Here I share with you our story “The Lady in apartment four-0”.

It’s said that ghosts are spirits that haunt places. Actually, the exact opposite is true. Ghosts are the ones haunted by places. I should know. I happen to be one.

You’ve all heard stories about places stricken by tragedy that have become the wandering ground of tormented souls that died violently or suffered terribly there. These places exist, to be sure. Souls go back to the places that marked them most. Yes, they weep and, yes, they can be scary. However, no one ever talks about the happy souls, those that come back for all eternity—or at least a part of it (What can I say? In the state we’re in, we lose all sense of time.)—in the place where they were at peace, the place where they lived in dignity like nowhere else. The place where they got a taste of what the living call “happiness”.

That’s the case for me.

The first time I came to the Château Laurier was in the early nineties. I was, oh… fortyish? I’m no longer sure. Anyhow, I was running away. From Toronto, its noise, its dust, how it swelled with pride and overshadowed Lake Ontario. I was also—especially—running away from my daughter. My daughter who went around telling anyone who would listen that my mental health was too fragile for me to look after her father’s fortune. My daughter who forced me to see doctors who wrote up foregone reports, doctors who wanted to send me to rot in a hospital amid the squeaky wheels of trolleys and stretchers. My daughter who sicked notaries on me to have me sign powers of attorney and statements of mental incompetence. Ah, she sure was foxy, my daughter. She was determined. My husband had been ill for only a short while when she began to spread those dreadful lies about me. She hammered the message to my sister-in-law, her husband, and my friends. People started speaking to me very softly as if they were afraid I might flip out and attack them like some mad dog. They started to avoid me, to look at me askance. Depressed, that’s what she went around saying about me, that I was chronically depressed. She brandished neurotic psychosis about like a bogeyman. In so doing, she became my bogeyman.

So I did what I had to do. I left town after making sure she wouldn’t get her greedy hands on even a single penny. Not one. Ever. Of course, things didn’t go as planned. But it doesn’t matter anymore, not now. She can very well do as she pleases. To hell with her.

I arrived in Québec City by train and hailed a cab to Grande-Allée. I had read an article about the winter carnival in Maclean’s, I think, and there was a photo of this picturesque avenue, snow-covered, all lit up, full of cheery ruddy-cheeked faces. A friend of my husband had told me once that it was the most beautiful city in Canada. That’s why I headed there. I’d also been told it was a quiet city with no hell-raking. A city where the living was easy. A city small enough to escape the noise, but big enough for someone to remain anonymous.

The cab dropped me off in front of St. Patrick’s. I walked eastward the entire length of the street up to the National Assembly with my little suitcase in hand. I stopped to examine the building overlooking the old ramparts. The autumn rain wetting the asphalt amplified the echo of the clip-clop of a horse drawing a carriage with a smiling young couple evidently very much in love. Everything seemed to be moving in slow motion. The cars—so fewer than in T.O.—the tourists, the public servants, the tall elms, they all yelled out to me: This is it, this is where you’ll be happy. For the first time since what seemed like forever, I felt relieved. I pivoted, slowly. A calèche driver was standing next to his carriage, scratching the neck of a horse at rest, its nose deep in a feedbag. The Saint-Louis gate opened onto the old city, framing it like a postcard. On the other side of the street, the Armoury beamed its neo-gothic facade. Behind it, you could make out the yet green grass of what I figured were the Plains of Abraham. And, right at the corner of the street stood a small Queen-Anne-style building whose aspect, I couldn’t say why, immediately struck my fancy. Was it the soothing charm of the brickwork? The quaint turret? The oriel windows? The stairs leading to a tastefully ornate wooden door? How can you tell what causes love at first sight? A sign read “Hôtel Château Laurier”. I liked the idea of living in a château. I crossed the street, climbed the wooden steps, and walked in.

I stayed for five years. The five happiest years of my life.

Of course, I didn’t give my real name. No credit card, either. I offered to put down a sizeable deposit. They set me up in a nice room overlooking the street. It was a modest room as I didn’t know how long I’d be staying. I had a tidy sum on me but I knew it wouldn’t last forever. I plonked my suitcase on the bed and went back down to eat. The atmosphere that reigned here was calm and muffled and filled me with an inner peace that I didn’t think I would ever enjoy in my mortal days. That night, I slept like never before. The fear that had always hounded me like a hideous gargoyle vanished.

Next day, I went out to get a few things: clothes, cigarettes. And a notebook. I ended up filling so many of them, I lost count. When I was done with one, I’d go out to get another. I knew that the housekeeping ladies eyed my notebooks. It intrigued them to see me writing in them all the time whenever they came to clean or bring up fresh towels. I wasn’t writing anything important. Thoughts, whatever crossed my mind. I committed to paper all the things I hadn’t dared tell anyone over the years.

Nice people, those ladies. The entire staff, actually. You got the impression that they were treated well here. That the work they did was appreciated. One of them, in particular, I liked a lot. Her name was Michelle. A big, beautiful woman with a radiant smile, bright eyes, intelligent and cheerful. Reserved but always friendly, without being informal. You could tell she was a fighter, that one. I would have liked to have been like her, brave and bold. The only time I showed any courage in my life was when I took off for Québec City. And even then, I wasn’t driven so much by courage as by fear. But let’s move on. Now I know everything there is to know about Michelle. I also know all there is to know about the history of this place that I chose as my residence.

I know that the current manager, a pretty young lady of thirty years, is the founder’s grand-daughter and that she practically grew up in the hotel. I know that Michelle watched her grow up. As it happens, Michelle has been at the hotel thirty years now. The lovely Michelle, this brave, bold and intelligent woman, who was hired initially at seventeen to service the rooms, today holds a key position in the hotel hierarchy after earning the trust of the owners. You can tell that there’s love between bosses and staff here. The people here are loyal, they stay on a long time. I think that the sense of calm that washes over you here has much to do with that.

The walls tell me everything. From the building’s construction at the end of the nineteenth century up until the major expansion work in recent years. I see the arrival of that family, in the mid-seventies, too. You had to think big to buy this building after leaving the Lac Saint-Jean region, where the prosperity of the forest industry no longer sufficed to ensure a comfortable lifestyle for everyone. They left, man, woman, and children, and settled in Québec City with their savings. The man began working in real estate, discovered he had a flair for the business and— presto!—he bought the Château-Laurier, which at the time was nothing more than a modest establishment, the kind you see in films noirs, with a wood reception desk and pigeonholes for stuffing messages in on the back wall, a small hook over each one for hanging keys. Over the years, they bought adjacent houses, made new rooms and even small apartments. The son took over the business in time and, now, the grand-daughter. When I lived here, the founder, who had passed away by then, at times came back to take a nap in the afternoon in a room that was kept just for him. The staff treated him with affection. That touched me.

I seldom left my room. I was fine here. Felt safe. Every day, I read in Michelle’s eyes that I was home here and that I would not be bothered. No one sought to trouble my peace or to uncover my secret. Each morning I would step out to get a pack of cigarettes at the corner convenience store and then went back to my room to write. I ate out sometimes, but that was rather rare. I was just fine in my château. I felt here like a princess secluded on her country estate.

After a few months, I was offered to move into one of the small apartments on the ground floor. It’s cheaper than renting a room by the day. I figured that, this way, my tidy sum would indeed last longer. So, I settled in apartment four-o, facing the Plains. The view wasn’t anything spectacular. But my dwelling opened onto a quaint little inner courtyard where I could, whenever I felt like it, go walk around and stretch my legs. Michelle and the other employees continued to ensure my well- being and tranquility. On summer nights, I could hear through my open window the clatter of tired horses returning to the stable at the end of a day spent looping through the same course for marvelling tourists. They were my connection to the outside world, the horses were. The echo of their clip-clop led me to every corner of this old city that I never visited otherwise.

Then, one day, my daughter tracked me down. She had put a private investigator on the case, I think. How long had she searched for me throughout the land before finding me here? How did she pick up my trail? I remember feeling a strange sense of victory for having been able to keep her at bay all those years. She landed with her papers drawn up by notaries and doctors, asked to see the lady in apartment four-o, and took me back to Toronto. I didn’t put up a fight. I was tired. I was taken to a very nice home where qualified people looked after me to the end. I don’t know what she did with my notebooks. Did she read them? Burn them? Frankly, I don’t give a damn.

Apartment four-o no longer exists. The hotel was expanded and modernized. There are reception halls now and new rooms along with others that kept a more vintage style. The restaurant is gone but catering services are offered and you can order room service from an establishment next door that serves barbequed chicken.

I’ve taken up residence in the presidential suite. Don’t ask how I got here, I have no idea. All I know is that at one point my spirit left my body and found itself here where I had known serenity. All sorts of people stay at the suite—dignitaries, celebrities, and ordinary folk alike. I get a big kick out of watching them live, but I never bother them. I suffered so much from people not respecting my quietude, the least I can do is respect that of others. It’s a wonderful place, very bright, with huge bay windows looking out onto the Plains of Abraham that I had only guessed were there when I was alive and that I can now behold to my heart’s content. I see families strolling about, people practising various sports, others picnicking. In the winter, the dark silhouettes of the tall elms watch over the guests’ slumber like benevolent ancestors.

Michelle comes sit on the leather couch sometimes when the suite isn’t occupied. She settles down a few minutes, long enough to breathe out into the bountiful light flooding in through the large windows. She meditates, goes over the week’s agenda in her mind, reflects upon decisions to be made, or simply clears her head a little before going back to work. She’s the one in charge of the other employees. She looks after everything. And I look after her.

Sometimes, I sit next to her and listen to her memories. She’s seen it all in the thirty years she’s been here, Michelle has. The wild nights of Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, when the gawkers came back from the bonfire like people possessed, the riots, the political summits, the parades of the Carnaval and the snow sculptures in front of the Armoury. She also saw it go up in flames, the Armoury. She contemplated the sad sight of the smoking stones in the wee hours of the morning. She heard the cries and smelled the smoke bombs of the Summit of the Americas. She has handled party animals and rowdies, on guard at all times to preserve the peace for the people that choose to hang their hat here for a few days, months, or years. She always did what she had to do with the calm, patient strength of someone who knows the value of a job well done. Born into comfort, I admire her. I see this woman who arrived here as a wide-eyed adolescent offering her physical vigour and what she’s become. A judicious person who can be counted on without fail. Everyone here has the utmost respect for her, not to mention tremendous affection. She now holds all the keys to all the doors, but I know she remembers well that time in her youth when chambermaids threw the dirty linen out the windows into the inner courtyard, too embarrassed to be seen carrying the bundles to the old laundry by way of Grande-Allée. She remembers when they allowed her to take her children along on her housekeeping run when they couldn’t go to school. She remembers the little two-year-old girl who wobbled to her with open arms, laughing, and who is now her boss.

She’s such a nice person, Michelle is. When I sit next to her on the couch in the presidential suite, I can feel it. She’s at peace with herself. Just as I am.

Marie Christine Bernard is a writer and a professor of literature. Her books have allowed her to travel just about everywhere in the world and to visit and assess all sorts of hospitality establishments, from the most modest to the most lavish. Her credentials and knowledge of the industry rest on two legs. First, she was raised in Carleton-sur-mer, in the Gaspésie region, a tourism hotspot since the 1850’s. Second, her family has owned a hotel there since 1979 and ran a restaurant there for some twenty years ranked among the top one-hundred in Canada. It would have been a crime not to have her contribute a short story to this collection.